27. April, 2021

Git aliases

By Lars Kruse

#git #gitops #gitalias #gitconfig #bashscripting #semanticversioning

Git aliases are mostly used for nifty shorthand variants or combinations of existing git commands. But aliases can do anything that you can fit into one line - literally. This also makes them fun bash scripting exercises - and inconceivably powerful.

This blog contains quite a few git tricks, tips and even a recommended automated GitOps workflow. It’s specifically detailed in terms of git aliases and utilization of git config. I’ve provided a short Table of Content so you can prepare for what’s comming.

Content

- Git the basics

- Stepping it up a bit

- Taking aliases to the next level

- Git Config team collaboration - fixing the missing level in git config

- All in All - the final config file

- How to install

Git the basics

Aliases

Good git aliases are like collectors items. They are one-liners, that makes your life (the git related part of it) much easier. They are literally one line statements. Here’s a short classical example:

git config alias.co 'checkout'

Now I can run git co as a shorthand substitute for git checkout This is a very popular use of git aliases - it saves me six chars every time I want to checkout a branch.

Tab completion

Tab completion is another nifty git feature worth mentioning when the talk is on optimizing your flow in git. In some git distributions it works out of the box, in others it needs a bit of tweaking to be ignited. What it does is simply, that it finishes your git commands for you. If you type the beginning of a git command and then hit <tab> it will toggle through the options you have and when you found the one you like you hit <enter>.

If I use tab completion then it turns our that I had no need for the co shorthand for checkout that I just created; I could already checkout with the same amount of key strokes (6): git co<enter> = git c<tab><enter>.

“OK! No revolution yet, but hang on a bit, it gets wilder”

Git config

A word on the git config command too: It’s essentially nothing but an in-line ini-file editor/reader of what is in your git configuration files. Git comes with knowledge of three system files; one is local (default) and resides in the repository: /.git/config another one is global and is in your user home folder: ~/.gitconfig, and the last one is system and sits in the /etc/gitconfig folder (I’m using *nix style locations - get an in-depth understanding of config files here).

git config --local ... #writes to .git/config in the .git folder 'underneath' your repository

git config --global ... #writes to ~/.gitconfig on your PC

git config --system ... #writes to /etc/gitconfig on your PC

So looking at the consequences of the previous git config command that created the alias it ended up in the .git/config file in the repository that was in the path when I executed it looking like this:

[alias]

co = checkout

…In fact could just have hacked that file directly in my editor, changes will take effect instantly when you save the file - I often find myself editing the config files more often than using git config.

Stepping it up a bit

So let’s find a more useful use of aliases - check this next one. I’m storing useful - but hard to remember - git command (scroll the code block to the right - it’s long!)

git config --global alias.tree 'log --graph --full-history --all --color --date=short --pretty=format:"%Cred%x09%h %Creset%ad%Cblue%d %Creset %s %C(bold)(%an)%Creset"'

“Really! That looks complicated!”

Well yes, and no. This is a brilliant example of how aliases really are useful.

The built-in log feature has some beautiful display features, and using the --pretty switch you can draw ASCII art trees of your branches and commits that really are - well artful. But no one wants to write, or even remembers, this relatively complicated format: string. Now I’ve created an alias called tree which since then has become my personal all time favourite git command.

And here’s a few bonuses: First: The tab completion feature has built-in knowledge of my aliases. so git tr<tab> will expand into git tree and second: Since the tree command is a variant of the log command it still supports all the switches that log does. As an example; log supports the switch -<number> to limit the depth of the log to <number> items. So my tree command also supports -<number> out of the box. To see my git tree 32 commits deep I’ll execute:

git tree -32

…and get:

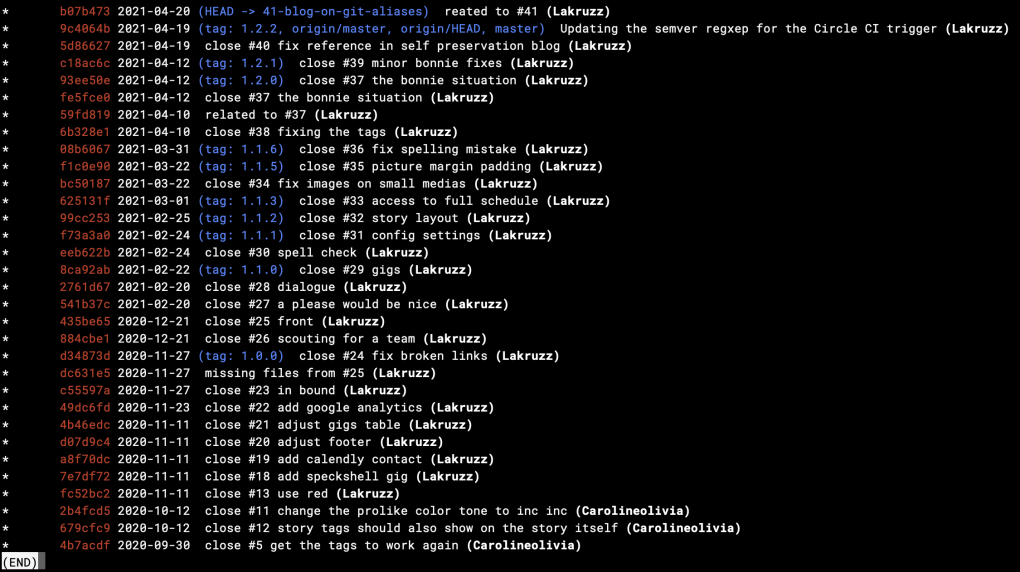

What you see is the history, 32 commits deep, in the repository that holds the website you are reading. it shows my commit SHA1s, the dates, the branches, the tags, the commit messages and the committers - exactly one line per commit. I don't have many branches in my repo; Since I minimize work in progress and always release from

What you see is the history, 32 commits deep, in the repository that holds the website you are reading. it shows my commit SHA1s, the dates, the branches, the tags, the commit messages and the committers - exactly one line per commit. I don't have many branches in my repo; Since I minimize work in progress and always release from master, but if there were a pile of branches, they would have shown in ASCII art to the left. Tree is now a pretty cool alternative to plain git log -32 and even an alternative to some of the graphical interface gitk. (click image to open full-size in a new tab)Git aliases vs git extensions

An alternative to git aliases are git extensions. They behave very much the same way. A git extension is merely an executable - usually a script - that is made accessible from your $PATH and which follows the naming convention that it must be prefixed with git- so if I create the script git-co like this:

#! /bin/bash

git checkout $@

And put it in /usr/local/bin - which is already in my $PATH - then I get the exact same result: git co is now shorthand for git checkout. And even git extensions are also automatically supported by tab completion, so as a git user, you wouldn’t know the difference if it was implemented one way or another.

“OK, then why do we have both?”

Well because one is light-weight and the other can hold unlimited amount of complex code. A git alias is limited to one line, that is; It can potentially contain more then one statement (I’ll show you in a bit), but it can not span more than one line. It’s literally a one-liner.

An extension is used when you want to extend git, not just with nifty shorthand variants and cute tricks, but entire landscapes of new features. Git’s graphical display tool called gitk is really a quite extensive (12K+ lines of code) executable called git-gitk written in Tcl/Tk.

Taking aliases to the next level

Let me introduce a nifty feature: Full support of semantic versioning in all your git repositories that might seem quite complex, something that would require a full-blown git extension (and there are quite a handful of them out there on the internet, which proves that the feature is popular and useful) but which turn out, can be actually be implemented in just two lines of code, and stored as aliases.

“No! Really?”

“Yes! Really!”

Implementing support for Semantic Versioning

SemVer Basics

It's essentially a naming convention, a protocol, in which you define version numbers in three levels of integers separated by dots:<major>.<minor>.<patch>

Then you play by the SemVer rules which goes as follows: When you make a new release, you bump one of the three levels. The semantical meaning of the three levels are as follows: Major is bumped if your release has features that breaks backward compatibility (e.g. a function that used to return a string now returns an integer). A bump of Minor also indicates that your release contains new features, but that they are backward compatible (e.g. the original function that returned a string is untouched, instead a new one is added, which returns an integer). And finally a bump in patch indicates that no new features were added, only bugfixes or enhancements to existing ones.

Another rule in semantic versioning is that if you bump a level, then all other lower levels are reset to zero using 1.2.3 as an example:

Bumping major in 1.2.3 becomes 2.0.0.Bumping minor in

1.2.3 becomes 1.3.0.Bumping patch in

1.2.3 becomes 1.2.4.

SemVer's obvious use case is in versioning interfaces or individual component releases, where the protocol lays the foundation of programatically determining wether or not it's safe to update a given component or not. SemVer is the most important tool in the toolbox, when striving to kill the a bloated monolith system compound into multiple nimble individual component releases.

I will not make this blog about Semantic Versioning (SemVer) in general, but specifically about how to implement it in just two lines of code, using git aliases. So I assume that you’re familiar with the concept - if not read up on it in the short recap in the fact-box.

It’s my belief, that a good workflow is one that is simple and easy to use. Sometimes workflows aren’t simple and easy to use, and in context of git and git related workflows (e.g. GitOps) git aliases (…and git extensions) are a brilliant and obvious way to simplify a workflow so that every team member has a few everyday git favourite git commands which are shared among every temmember, and essentially implement the workflow - nice and easy. So before getting to work, I’ll just set the scene and put a few words on the workflow I use and advocate.

I assume the following:

- I’m working in a Centralized Distributed Workflow This is typically the case for all team using a git-as-a-Service platforms (mine is GitHub but any will do).

- The repository has a declarative pipeline defined which monitors certain events in the centralized repository (mine is in Circle CI but any will do).

- The declarative pipeline implements “GitOps” That is; When something happens in git, then stuff is automatically verified, promoted or deployed. I have three actions/levels in my repos:

- Ready: Any new commit that arrives on a branched prefixed with

ready/is automatically rebased againstmasterand verified. If the verification is successful it’s automatically merged (guaranteed to be fast-forward, since it’s already rebased) tomaster - Master: Any new commit that reaches the

masterbranch is automatically verified - and if flawless - deployed to the stage environment. - SemVer: Any commit that is tagged according to SemVer rules is automatically verified and deployed to the production environment.

- Ready: Any new commit that arrives on a branched prefixed with

WTF! - No Pull Requests?

It’s worth noticing that in my workflow I don’t use pull requests. The reason is really that while the generic concept of a Pull Request (PR) undoubtedly exists, it is nevertheless implemented differently in GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, Azure DevOps, each in its own proprietary implementation. And on top of that PR’s were originally designed, to support a Benevolent Dictator Governance Model (BDGM) in which only the Benevolent Dictator For Life (BDFL) and the trusted lieutenants have write (push) access, and all other contributors were potentially seen as riff-raff and they would have read (pull) access - but not write access. To contribute they would then have to fork or branch the code, make the code suggestions and then place a Pull Request with one of the trusted lieutenants, who would then read and validate the code for your, and if accepted then they would pull it in. Quite a cumbersome and manual process. And in the light of the fact that in most of todays git repositories, all contributors already have write access, it seems like it’s an obvious thing to optimize.

Let’s have a look at what a pull request is generically and why it may have survived and remained popular in many teams despite almost no one today works in a Benevolent Dictator Governance Model anymore. Generically, a PR is implemented as a short-lived temporary branch related to a specific increment (task) that needs some level of verification before merged into another branch - usually master. This is no different than the flow I advocate, where we say, that any code change must be done on a separate short-lived branch and only accepted into master if quality measures are sufficiently met. So consequently, my ready/ branch is like a pull request, It’s simply a way to signal to my automated GitOps backend that I’m ready to take the test and see if my code is worthy of being integrated onto master. The advantage I get is that I’m only git native features - in this case simply a dedicated short-lived branch and a self-made naming convention. So consequently my setup is compliant with any Distributed Centralized Git repository strategy - including all the popular git-aaS-platform mentioned earlier.

Nah! You’re missing out on reviews!

Yes, since I’ve taken PR’s out of the equation what I often get is: “Hey, you can’t do that, what about peer reviews then?”

And it’s true that in most teams Pull Requests are associated with, or sometimes even a synonym to, code reviews. But in my world - if a code review is required - then it’s performed directly on the short lived issue branch - all the different git-aaS-platforms have perfect built-in support for annotated reviews. It’s easy! And it has the desired side-effect that getting an extra set of eyes on the code in the development process turns it into a collaboration process among peers. And remember: Peers are equals! They are not supposed to be each others gate-keepers. The flow I advocate has a sent of paired programming among peers or the same flow can be used in a lean Senpai and kōhai inspired relation where a master takes responsibility for an apprentice.

The choice to ditch reviews as quality gates and to only use native git commands as opposed to proprietary implementations of Pull Requests has to do with my general admiration of the concept of lean and automation. A review, regardless if it’s done by a peer or a mentor, can’t possibly be automated, since it requires a reel persons sincere opinion. Essentially this makes the review belong to a validation process as opposed to a verification process. For that reason it can not possibly become part of the process that’s supposed to run automatically - as it would inevitably introduce a wait state - an in lean processes waiting is considered waste. I’m not adding waste to my flow - I’m removing it!

My workflow is simply workon and deliver

When a task is assigned to me (I’ll use issue #34 as an example), I create a shot-lived branch for the task and implement my solution. The way I do this is to run git workon 34 but that’s because I’m using a git extension that supports git workon I’ll leave that for a later blog post. I’t essentially roughly the same as:

git checkout master

git pull

git checkout --track origin/master -b 34-my-short-lived-issue-branch

I’m now on branch 34-my-short-lived-issue-branch and I then start hacking my solution. If I need feedback or an OK from a peer or a mentor before I can deliver to the automated pipeline then I’ll commit with a mention of my colleague and push is to the centralized repository (origin) - like this:

git commit -m "Hey @DenverCoder32 - please look at his"

git push origin 34-my-short-lived-issue-branch

If I’m on any of the popular git-aaS-platforms - then the mention of my colleague in the commit message will trigger that she gets a notification with a link to the commit, and she can go and annotated her comments or review on my commit, exactly as if it was one of the proprietary pull request implementations.

When I’ve gotten the feedback from my peer or mentor - or if I don’t need it - then I deliver to the automated pipeline simply by pushing the branch again - I have a git extension installed allowing me to do git deliver it will simply prepend the branch with ready/ in the push process - it plays roughly something like this:

git push origin 34-my-short-lived-issue-branch ready/34-my-short-lived-issue-branch

The name ready/ triggers my pipeline. If all is well then the rest is really as automated - and boring to watch - as a washing machine wash.

Using Circle CI as an example, here’s how my pipeline is defined:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

- deliver:

requires:

- prep-repo

- jekyll-build

filters:

branches:

only:

- /ready\/.*/

- stage-deploy:

requires:

- prep-repo

- jekyll-build

- html-proofer

filters:

branches:

only:

- /master/

- prod-deploy:

requires:

- prep-repo

- jekyll-build

- html-proofer

filters:

branches:

ignore: /.*/

tags:

only: /^.*\d+\.\d+\.\d+.*$/ # Contains a Semantic Version number

In case you’re not that familiar with Circle CI but are more proficient in one of the many other declarative pipeline technologies I’ll give you a quick run-down of what’s going on in the YAML snippet above so you can do something similar in GitHub Actions, Azure Pipelines, GitLab CI, Jenkins - or whatever declarative pipeline you are using - they all support something similar.

I have defined three alternative paths in my flow. All stages apparently do the same two steps to begin with (lines 3+4, 11+12 and 20+21). prep-repo rebase from and then fast-forward merges the commit into master if it isn’t there already and generates a version.txt file, which I can include in the release. It then caches the repo on Circle CI infrastructure for potential reuse. jekyll-build builds the static website with Jekyll and caches only the derived HTML - that is the result not the source - again for potential reuse. The results from these various stages are cashed with reference to the SHA1 of the commit, so if I re-run the same commit, the two stages are reused rather than replayed.

In addition to prep-repo and jekyll-build the two deploy stages also requires a flawless html-proofer (lines 13+22).

The deliver flow is triggered only by branches that are prefixed with ready/ (lines 6-8). The stage-deploy flow is trigger only by the master branch (lines 15-17) and finally then prod-deploy stage is triggered not by branches, but only tags that contains a SemVer pattern (lines 24-27).

So the ready/ branch from before triggered the deliver flow, which ended up merging onto master which then in turn triggered the stage-deploy flow, which reused the prep and build and in addition checked for dead links and if successful automatically deployed to my stage environment, which is a real-time live production-like environment.

This is my own website, but had it been a product with a customer/product owner who needed to validate before deploying to production, then I could point them to the updated stage environment and wait for their approval and simply set a SemVer tag and push it. It could look like this:

git tag -a -m "Making a patch bump on 1.2.3" v1.2.4

git push --tags

This would trigger the prod-deploy workflow - which would again reuse the prep and build steps and then deploy to production being the website you’re reading now.

And this is where I now need a tool to help me

When I run the

When I run the git tag command it lists all the tags I have in my repo - but I'm really only interested in one with the highest SemVer value.To get my next SemVer tag, regardless of what level I want to bump, I need to know the previous level. I do:

git tag

And I would then seek out the one with the highest SemVer value - in this case it would be 1.2.4 which I can tell from the rather inconsistent use of naming in tag version_1.2.4_some_comment. What really could be helpful would be a git semver command which simply replies 1.2.4.

It turns out that this is quite easy to get from a shell command like This:

git tag | grep -Eo '\d\.\d\.\d' | sort | tail -1;

OK, not very complicated, but still complicated enough to be cumbersome to type each time I need it.

Storing bash scripts as one-line git aliases - using closures

If the alias expansion is prefixed with an exclamation point, it will be treated as a shell command.

So I could create a semver alias like this:

git config --global alias.semver "\!git tag | grep -Eo '\d+\.\d+\.\d+' | sort | tail -1"

But git aliases also automatically passes an any parameter to the execution. This is sometimes desired, as we saw in the tree alias previously, where the switch supported by git log was also automatically supported by git tree.

But sometimes it’s not desired - sometimes I don’t accept parameters or switches, and I want them to be swallowed or ignoreed and sometimes (as you’ll see later) I want to pass parameters or switches to the alias itself, not it’s execution.

So the semver implementation above would mean that an execution like git semver some_rubbish_parameter would make it fail, whereas I would like the rubbish parameter to be ignored.

The trick to achieve this is instead of defining the execution, we define a function, that does the execution, and then we execute the function - a trick that’s know as a closure. This way we get to manipulate or investigate any input before it’s unconditionally executed

The closure construct in bash looks like this:

#template

f() {statement-1; statement-2; ...; statement-n; }; f

# semver as closure

f() { git tag | grep -Eo '\d+\.\d+\.\d+' | sort | tail -1; }; f

But before we store it, let’s consider, what happens if there aren’t any SemVer tags set yet, if we’re the first developer here. Aaarh! Nothing is returned, so bumpsemver has nothing to bump. Let’s fix that. Some teams wants to start the SemVer with 0.0.0 others with 0.9.0 or 1.0.0. Let’s store the team’s initial preference in the config file in a new section called [semver]`- something like:

git config --global semver.initial 0.0.0

And then let semver return that if the grep command doesn’t catch anything. OK! One down - git semver is in the box - it ended up like this:

git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig alias.semver "\!f() { SEMVER=\`git tag | grep -Eo '\\d+\\.\\d+\\.\\d+' | sort | tail -1\`; if [ '_' == _\$SEMVER ]; then echo \`git config --get semver.initial\`; else echo \$SEMVER; fi; }; f"

# >> Scroll to the right - it's long >>

Now it always gives me the current SemVer, regardless of how inconsistently I named my tags. And if there’s no match I gets the number from the config and returns that .

Getting a bit ugly - adding support for parameters and switches

Next up is a git bumpsemver command which I’d like to take one of three possible switches, indicating which level to bump. I would then like it to type out - but not execute - the command that I would use to the next SemVer label. Having it type out rather than execute it means that it would always be safe to (test) run the command, and If I like it, I can just rerun it inside an eval $( ...) construct.

As show in one of the previous examples, when I set my SemVer tags I always make them annotated and I always provide a message, usually I mention what the previous SemVer was - so keep a bit of history something like:

git tag -a -m "minor bump on 1.2.3" v1.3.0

But others might want to apply their own messages. So my decision is, that I need git bumpsemver to take an additional but optional parameter, which will become the message to -m. If no message is applied, then bumpsemver should automatically generate something similar to the example above.

I’ve also seen many software teams prefix their SemVer with v or ver like v1.3.0 or ver1.3.0 so I wan’t to have support for that too. I’ll create a prefix setting for this and put it in the in semver section. So if you want a prefix v it should be set like this:

git config --global semver.prefix v

Which would total the semver section in the config file to look like this:

[semver]

inital = 0.0.0

prefix = v

And finally, on top of everything, I’d like the alias to be so clever, that if I execute it wrongly, it does nothing wrong, but instead it just shows a nice and short instruction on how to use it correctly something like:

$ git bumpsemver

Usage: git bumpsemver --major|--minor|--patch [msg]

Generates the git command to run. If you omit

the [msg] a clever one will be generated for you.

To execute it run it in an eval $(...) like this example:

eval $(git bumpsemver --minor "this will be the comment")

That’s what I want, nothing more, nothing less. All in just one line of code - as a git alias.

It’s not as daunting a task as it seems. First I’ll lay it out as it looks in a neat bash closure, and then we’ll weed out the new-lines and escape whatever needs to be escape for persistent file storage. I give you git bumpsemver dressed up as a closure:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

f(){

PREFIX=$(git config --global --get semver.prefix);

if [ -z \"$2\" ];

then MSG="-m \"$1 bump on `git semver`\"";

else MSG="-m \"$2\"";

fi;

levels=(`echo \$(git semver) | tr '.' ' '`);

if [ '_--major' == _$1 ];

then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX$((${levels[0]}+1)).0.0;

elif [ '_--minor' == _$1 ];

then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX${levels[0]}.$((${levels[1]}+1)).0;

elif [ '_--patch' == _$1 ];

then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX${levels[0]}.${levels[1]}.$((${levels[2]}+1));

else echo 'Usage: git bumpsemver --major|--minor|--patch [msg]\n

Generates the git command to run. If you omit

the [msg] a clever one will be generated for you.

To set the tag run bumpsemver inside an eval $(...) like this example:

eval \$(git bumpsemver --minor \"this will be the comment\")';

fi;

};

f"

There’s quite a few cheap bash tricks in play here - so if you are curious to what happens I’ll walk you through it.

Line 2: As mentioned earlier, git config is also a reader. So the script simply reads whats in the file ~/.gitconfig file.

Lines 3-5: The -z switch to the file test is TRUE if the variable is not defined. If no messages is applied then a default one is generated, if a message is given then it overrides the default message - mentioning the current SemVer level by reusing the git semver alias.

Line 7: tr replaces dots with spaces - and returns an array. tr splits on spaces so 1.2.4 becomes a three item array [1][2][4] and an arrays is what is needed in (lines 9, 11 & 13). Also notice, that bumpsemver is reusing the semver alias.

Lines 8,10 and 12: A dummy _ char is added in the comparison on both sides, otherwise the script would fail if no parameters were applied - comparing something to noting, and we want that failure to be a friendly usage statement in line 14.

Lines 9,11 and 13: Type casting $levels with ${...} allows us to access the array items. And type casting the sting to an integer using s((...)) allows us to use arithmetic operators, so we can increment the level.

Now let’s wrap this up - it’s a bit ugly, but we have to fit it onto one line - be warned:

git config --global alias.bumpsemver "\!f(){ PREFIX=\$(git config --global --get semver.prefix); if [ -z \"\$2\" ]; then MSG=\"-m \\\"\$1 bump on \`git semver\`\"\\\"; else MSG=\"-m \\\"\$2\\\"\"; fi; levels=(\`echo \$(git semver) | tr '.' ' '\`); if [ '_--major' == _\$1 ]; then echo git tag -a \$MSG \$PREFIX\$((\${levels[0]}+1)).0.0; elif [ '_--minor' == _\$1 ]; then echo git tag -a \$MSG \$PREFIX\${levels[0]}.\$((\${levels[1]}+1)).0; elif [ '_--patch' == _\$1 ]; then echo git tag -a \$MSG \$PREFIX\${levels[0]}.\${levels[1]}.\$((\${levels[2]}+1)); else echo 'Usage: git bumpsemver --major|--minor|--patch [msg]\n\nGenerates the git command to run. If you omit\nthe [msg] a clever one will be generated for you.\nTo execute it run it in an eval $(...) like this example:\n\n eval \$(git bumpsemver --minor \"this will be the comment\")'; fi; }; f"

# >> scroll - it's very loooong >>

Git Config team collaboration - fixing the missing level in git config

OK, now I’ve given you an handful of useful git aliases, and git config settings. Now it would be nice, if everyone on the team, had these settings and aliases, then we would know that every team member was doing the same thing. As a team lead I could ask everyone to execute all the commands that would set these aliases. Or distribute a script that did it, but I admit, that the commands are delicate, they are not even white-space tolerant, the removal of just one tiny white-space might render the alias useless. And personally I favour the principle of Configuration as Code which mean that I would much rather distribute and version control a config file, as opposes to a script that sets the config file.

But there is kind of a missing level in the whole git config story. --system and --global levels are on the developers own PC and out of reach for version control. --local is in the repository’s .git folder which is kinda underneath it all and not included in the version control and general clone, pull, push, branch scope.

I kinda miss a fourth level in the whole git config setup, something like --repo that would get and set from a file .gitconfig which was located in the root of the repository, and then could be version controlled together with the rest of the team’s files.

And then I need git config to include this new fourth repo level in the equation.

First part is easy to achieve since the git config already supports that I can use the --file switch to write to any other file. So I could do something like:

git config --file <repository-root>/.gitconfig alias.co checkout

Hmmm, looks like all I need now is a generic way to get the repository root, something like git root. Such a git command doesn’t exist, but I can get the root with git rev-parse --show-toplevel and I can easily make it a git root command if I want:

git config --global alias.root 'rev-parse --show-toplevel'

Second part is to include the new config file in the git config hierarchy so it’s settings comes into play, I can use the include directive supported by git config it’s not 100% ideal, since I would have to put the include in one of the three default config files, and as discussed none of them are version controlled but it will work. Relative paths in the include directive takes off-set in the location of the config file itself, the --system and --global levels can’t really act as generic in regards of the repository location, as I may have cloned the repos to anywhere on my hard drive. So for this reason it turns out that the --local level has one advantage over the two other, as it always sits underneath the repository which mean that the repository level .gitconfig is always in the parent directory, relative to the local config file (remember it’s in the repository’s .git/config). So every git repository on earth, regardless of where it cloned to, has a valid --local include path that looks - like this.

git config --local include.path ./../.gitconfig

So if the team distributes their shared aliases and config settings in general in a .gitconfig in the root of the repository, where they probably already have all the other config files they share. Then the git config command above would then be the only command I would require for all teammates to run the same settings. Using the local level implies that it must be included and set in every repository. So the final alias I give you is one that reads everything in the repo’s .gitconfig and pours it into the --global and essentially make them all your own. It actually work as intended, since the local level is read last, and the include level is read as the very last. So any updates your team makes in the repo, would take precedent over your global ones. I’ve made the alias safe, so it won’t update your global settings if the are already defined.

git config --global alias.repo-config-to-global "!f(){ for f in $(git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig --list --name-only); do git config --global --get $f > /dev/null || git config --global $f "$(git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig --get $f)"; done; }; f"

If you want to use git repo-config-to-global to update existing settings, you do it by deleting them first and reapplying them from the one in the repoitory:

for setting in $(git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig --list --name-only); do git config --global --unset $setting; done;

git rep-config-to-global

# >> Scroll to the right - it's long >>

All in All - the final config file

It ended up like this:

[alias]

tree = log --graph --full-history --all --color --date=short --pretty=format:\"%Cred%x09%h %Creset%ad%Cblue%d %Creset %s %C(bold)(%an)%Creset\"

semver = "!f() { SEMVER=`git tag | grep -Eo '\\d+\\.\\d+\\.\\d+' | sort | tail -1`; if [ '_' == _$SEMVER ]; then echo `git config --get semver.initial`; else echo $SEMVER; fi; }; f"

bumpsemver = "!f(){ PREFIX=$(git config --global --get semver.prefix); if [ -z \"$2\" ]; then MSG=\"-m \\\"$1 bump on `git semver`\"\\\"; else MSG=\"-m \\\"$2\\\"\"; fi; levels=(`echo $(git semver) | tr '.' ' '`); if [ '_--major' == _$1 ]; then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX$((${levels[0]}+1)).0.0; elif [ '_--minor' == _$1 ]; then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX${levels[0]}.$((${levels[1]}+1)).0; elif [ '_--patch' == _$1 ]; then echo git tag -a $MSG $PREFIX${levels[0]}.${levels[1]}.$((${levels[2]}+1)); else echo 'Usage: git bumpsemver --major|--minor|--patch [msg]\\n\\nGenerates the git command to run. If you omit\\nthe [msg] a clever one will be generated for you.\\nTo execute it run it in an eval like this example:\\n\\n eval $(git bumpsemver --minor \"this will be the comment\")'; fi; }; f"

root = rev-parse --show-toplevel

repo-config-to-global = "!f(){ for f in $(git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig --list --name-only); do git config --global --get $f > /dev/null || git config --global $f \"$(git config --file `git root`/.gitconfig --get $f)\"; done; }; f"

[semver]

prefix = v

initial = 0.0.0

How to install

You have options:

Copy to config file

- Simply copy the content from the final config file shown above into your own - into your own config file

Run from terminal

- Clone my

lakruzz/semver_git_aliasrepo - Change directory to be inside the repo

- Include the

.gitconfigfile from the repo - Pour them into you own global level

Copy and run theses four lines:

git clone https://github.com/lakruzz/semver_git_alias.git

cd semver_git_alias

git config --local include.path ./../.gitconfig

git repo-config-to-global

I’ve put everything in a small git repository lakruzz/semver_git_alias. If you have any comments or want to share some of your own git aliases, then let’s chat up using the GitHub issues.